Taxing the Chinese

Canada passed its first Chinese Immigration Act in 1885, the same year Prime Minister John A. Macdonald was able to muster enough support in Parliament for an electoral franchise act that excluded persons belonging to the Chinese race, and fast on the heels of a Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration.

Justice John Hamilton Gray had recommended in his final report, as a commissioner to the Royal Commission, that the federal government impose a $10 tax on every Chinese man, woman or child disembarking from a ship at a Canadian port. Interestingly, it was Justice Gray who had earlier ruled against the constitutionality of British Columbia’s Chinese Tax Act, in Tai Sing v. Macguire (1878).

Parliament went a step farther, when it assented to the Chinese Immigration Act on July 20, 1885 to impose a $50 head tax on Chinese immigrants to Canada. The Act in its entirety placed an unequal financial burden on Chinese immigrants, attempted to limit new arrivals and interfered with the development of community services that responded to state-sanctioned racism.

Sections included in the Chinese Immigration Act (1885):

s. 4 “. . . every person of Chinese origin shall pay into the Consolidated Revenue Fund of Canada, on entering Canada, at the port or other place of entry, the sum of fifty dollars, except the following persons who shall be exempt from such payment, that is to say, first: the members of the Diplomatic Corps, or other Government representatives and their suite and their servants, consuls and consular agents; and second: tourists, merchants, men of science and students . . .”

s. 5 “No vessel carrying Chinese immigrants to any port in Canada shall carry more than one such immigrant for every fifty tons of its tonnage; and the owner of any such vessel, who carries any number in excess of the number allowed by this section, shall be liable to a penalty of fifty dollars for each person so carried in excess.”

More restrictions

While the former two sections of the Act are widely known, and regarded today as the most discriminatory aspects of the law as it was used against Chinese individuals, further restrictions on the Chinese Canadian community included:

s. 17 “Every person who takes part in the organization of any sort of court or tribunal, composed of Chinese persons, for the hearing and determination of any offence committed by a Chinese person, or in carrying on any such organization, or who takes part in any of its proceedings, or who gives evidence before any such court or tribunal, or assists in carrying into effect any decision of decree, or order of any such court or tribunal, is guilty of a misdemeanor, and is liable to imprisonment for any term not exceeding twelve months, or to a penalty not exceeding five hundred dollars, or to both . . .”

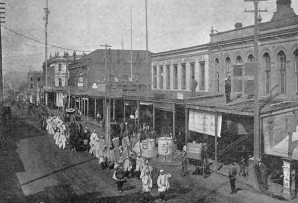

Section 17 was in all likelihood the Canadian government’s response to the establishment the previous year in Victoria, B.C., of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, which was a community initiative in the struggle for both individual and group rights for Chinese in Canada. The CCBA had a role in arbitrating disputes, which was allowed under the Chinese Immigration Act, within the Chinese Canadian community and advocating for justice in its interactions with broader society.

Restrictions were also put on naturalized and Canadian-born Chinese residents in Canada who had to pay a fee of 50 cents to register with local authorities. Travel by any Chinese outside of Canada, after paying the registration fee or the head tax, was also regulated by the government.

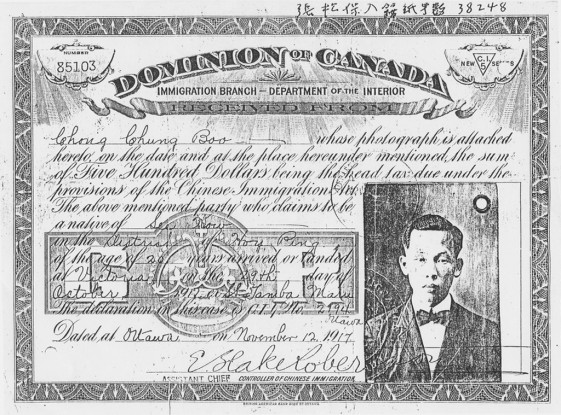

Head tax payers received receipts as proof of payment, as well as serving as an identity document that nonetheless could still be challenged by customs officers with the burden of proof lying with the accused.

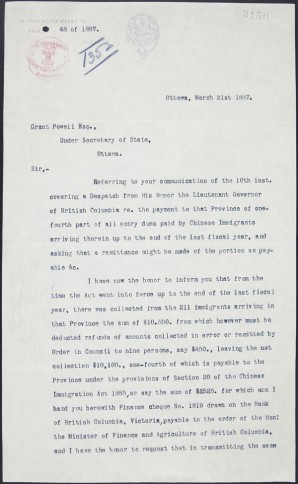

An accord was also struck between Ottawa and the provinces on collecting the head taxes on Chinese, and included hiring a controller to execute the duties of the Act and a portioning of one-quarter of all money collected being allocated to the provinces from the general treasury.

$50, $100 . . . $500!

The Chinese Immigration Act was amended on several occasions, with important changes in 1900, which doubled the head tax to $100 and required that Chinese leaving Canada must return within a year of departing or face paying the head tax again on their return.

The head tax must have created enough revenue that a 1902 amendment adjusted the provincial share of the tax to half of all revenues; British Columbia would have been the biggest recipient of proceeds from the head tax.

In 1903, the Act was amended again to increase the head tax to $500. The fee was deemed necessary at the time to stem the flow of Chinese immigrants to Canada. This undue burden on Chinese in Canada meant that many men, who had come here to work even before the head tax was imposed, would never be able to bring their families to Canada.

Family separation and dislocation became a reality for many Chinese in Canada at the time. The financial burden of the head tax, now at $500 (said to have been enough to purchase two houses in Montreal at the time), impoverished many Chinese.

Additional amendments continued to enrich federal and provincial governments.

Some exemptions were granted, while others were tightened up. In 1906, a clause was removed that had exempted servants of British persons from paying the tax if both parties returned to China within a year of landing. Two years later, only the “minor” children of merchants and clergymen were exempted; students were no longer exempt, but “duly certified” teachers could avoid paying the head tax. In 1917, the government granted stronger powers to tax controllers, giving immigration officials the right to arrest without warrant any Chinese believed to be illegally in Canada.

In 1921, the law was changed to state that every person of Chinese origin who leaves Canada without registering shall be subject to the $500 head tax, as in the case of first arrival; it added that absence from Canada could be no more than two years, otherwise payment of another $500 would be levied on return.

Restrictions on travel

Chinese who were resident in Canada had to be circumspect in their movement, particularly with respect to travel back to China for familial or business purposes, or on trips elsewhere.

In 1919, a Chinese named Fong Soon landed in court when he was charged with landing in Canada without paying head tax. Soon had paid the tax in 1901 when he first arrived, but in 1918 he made a short trip to Washington State. (see Key Court Cases)

A B.C. court held that Soon did not have to pay the head tax again, and that registrations for travel outside Canada were meant for those who traveled back to China, and not to the United States for a short period of time.

Letter to Under Secretary of State from Chief Controller regarding the amount of money owed to British Columbia provincial government resulting from Chinese immigration fees, March 21,1887

Government collects $23 million

The Canadian government and provinces profited from the hardships their legislation placed on the Chinese. The various head taxes collected over 38 years amassed some $23 million for the government; ironically, this was nearly the amount necessary to pay for the western section of the Canadian Pacific Railway, largely constructed by the Chinese.

Any hope among Chinese still in Canada of working hard to reunite their families was quashed in 1923, when the federal government received assent for an overhaul of the Act that abolished the head tax and simply prohibited Chinese immigration to Canada.